by Deborah Blum

Late last year, the news service Reuters reported a story with the headline "Prenatal Arsenic Exposure Quadruples Infant Death Risk." As the opening paragraph further explains, if pregnant women are exposed to high levels of arsenic, their babies are more likely to die in the first year than "infants whose mothers had the least exposure to the toxic mineral."

Late last year, the news service Reuters reported a story with the headline "Prenatal Arsenic Exposure Quadruples Infant Death Risk." As the opening paragraph further explains, if pregnant women are exposed to high levels of arsenic, their babies are more likely to die in the first year than "infants whose mothers had the least exposure to the toxic mineral."

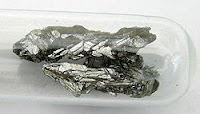

At first look, this might appear to be one of the world's most obvious findings. The element arsenic is one of the oldest known naturally-occurring poisons on Earth, found scattered through rocky beds of minerals around the place. It was reportedly identified by the Roman Catholic scholar and alchemist Albertus Magnus (also known as St. Albert the Great) in 1250 and almost immediately recognized for its homicidal potential.

The murderous Borgia family, of 15th century Italy, was notorious for its ruthless use of arsenic to eliminate enemies, but the Borgias weren't alone in recognizing its potential. Arsenic was so commonly used to remove unwanted relatives during the 18th and 19th centuries that it was nicknamed "the inheritance powder." A metallic element, arsenic kills by disrupting cellular metabolism to such a degree that it can literally poison every cell in the body. The body stores arsenic in tissues (bioaccumulation), meaning that it is dangerous both in acute and chronic exposures.

There's no surprise–and one might think, no news value–in the fact that prenatal arsenic exposure might pose a serious health risk. Except that this finding doesn't derive from one more neatly controlled laboratory study. It comes from what I'm going to call a living experiment, in which the test subjects turn out to be human beings and those statistics about infant risk are actually based on tallying up dead children.

To explain: During the 1970s, international aid agencies came up with what seemed like a brilliant plan to stem a plague of water-borne illnesses in the Asian country of Bangladesh. Cholera, typhoid, dysentery were killing citizens by the thousand. As the pathogens responsible lived in surface water, public health officials decided the answer lay in cleaner supplies underground. Aid organizations joined together to install wells in disease-troubled villages, reaching down into the germ-free ground water below. They chose simple, relatively inexpensive tube wells, placed thousands of these over-sized drinking straws into the shallow aquifers.

To explain: During the 1970s, international aid agencies came up with what seemed like a brilliant plan to stem a plague of water-borne illnesses in the Asian country of Bangladesh. Cholera, typhoid, dysentery were killing citizens by the thousand. As the pathogens responsible lived in surface water, public health officials decided the answer lay in cleaner supplies underground. Aid organizations joined together to install wells in disease-troubled villages, reaching down into the germ-free ground water below. They chose simple, relatively inexpensive tube wells, placed thousands of these over-sized drinking straws into the shallow aquifers.

At first, it seemed to work like a blessing. Infant mortality rates dropped by 50 percent as the rate of water-borne diseases dropped. But by the mid-1990s, a strange epidemic of other illnesses began to appear–some symptoms rather like cholera (lethargy, severe stomach pain, nausea and diarrhea), but others wickedly their own: such as a roughening and darkening of skin, a corrosion appearance of lesions on hands and feet:

In fact, as a team of researchers from adjacent India concluded in 1995, these were classic symptoms of arsenic poisoning. As it turned out, no one had done a good geological survey of the bedrock surrounding the aquifers. And with the best of intentions, the live-saving wells had been drilled into area unusually rich in naturally occurring arsenic.

As an ingredient in the complex recipe that makes up the Earth's crust, arsenic is relatively rare, about 1.5 parts per million over all, and is usually brought to the surface as a waste byproduct of mining other ores. The problem is that it's not distributed evenly around the planet. Arsenic-dense mineral deposits cluster unevenly. To be fair, we often discover them only when illnesses appear; we now can state conclusively that one such region lies beneath the Ganges River Delta, where Bangladesh and the West Bengal province of India come together. Others are known in Thailand, Taiwan, in an underground swath across mainland China, in the Latin American countries of Chile and Argentina, and in states of the American West such as New Mexico and Nevada.

As a result, in Bangladesh, the nice little tube wells drew poison-laced water right into the homes and lives of millions and millions of people. Earlier this year the World Health Organization described the problem in Bangladesh as "the largest mass poisoning of a population in history."

This conclusion was reinforced by a comprehensive report in the British medical Journal, Lancet, which concluded that some 77 million Bangladeshi had been exposed to toxic levels of arsenic and that such exposure was responsible for more than 20 percent of the deaths in a population study group from the region. "The results of this study have important public health implications for arsenic in drinking water," the authors noted, with some understatement.

This conclusion was reinforced by a comprehensive report in the British medical Journal, Lancet, which concluded that some 77 million Bangladeshi had been exposed to toxic levels of arsenic and that such exposure was responsible for more than 20 percent of the deaths in a population study group from the region. "The results of this study have important public health implications for arsenic in drinking water," the authors noted, with some understatement.The use of well water has reduced the deaths from waterborne illness. It hasn't, as hoped, eliminated that problem. The rivers and streams of Bangladesh, too often contaminated by raw sewage, remain carriers of often deadly illnesses. And for this reason, many people living in the country still prefer to use well-water.

And for this reason, Bangladesh now serves a living laboratory for the study of arsenic exposure. The Reuters story is based on a study, "Arsenic Exposure and Risk of Spontaneous Abortion, Stillbirth and Infant Mortality" in last November's issue of the journal Epidemiology. "We observed clear evidence of an association between arsenic exposure and infant mortality," Dr. Anisur Rahman of Uppsala University Hospital in Sweden and colleagues wrote.

Let's call this exposure with a capital E. Some of pregnant women tested had blood arsenic levels above 1,000 micrograms per liter. In the United States, normal levels are considered to be between zero and 15 micrograms per liter. Do you wonder that all did not end well with those pregnancies? As Rahman points out, the mechanism for arsenic-induced infant mortality is not known and that further study might eventually yield some protective treatments for people living in poisonous regions.

But I suspect that these mothers would not have chosen to participate in this accidental experiment, and would far have preferred that we understand arsenic another way. I do appreciate that we try to gain from mistakes, get smarter, do things better. But the poisoning of Bangladesh also makes me appreciate a very old saying attributed to the 12th century French abbot, St. Bernard of Clairvaux: "L'enfer est plein de bonnes volontés et désirs." It translates, roughly, as "the road to hell is paved with good intentions."

Wow. Thanks for sharing. I can't believe this article. I am amazed that mineral could cause so much damage.

ReplyDeleteI always learn something new from your posts, Deborah. I'm almost finished with your great book, Ghosthunters:William James and the Search for Life After Death. It's absolutely fascinating and I can't stop talking about it to anyone who will listen.

ReplyDelete