I read Alda's thoughts as I was waiting for my luggage to find its way to the baggage claim at the airport in Baltimore, Maryland. Looking up, I noticed a number of forlorn suitcases waiting patiently for someone to come for them. There were about twenty in all, big and small, strewn about, unattended. Over the loudspeaker came the familiar warning to notify airport authorities if there were any unattended items left about. I looked over at the unclaimed suitcases and I thought, well, yes, there are twenty of them. Being a criminal profiler, I often evaluate a situation from from a criminal's point of view and I found it rather ironic that when we arrive at the airport we watch carefully for suspicious people - at the ticket counter, in the security line, or shopping in the stores - and we become immediately concerned if they suddenly walk away from their luggage, yet when we go down a level to the baggage claim, we don't pay a bit of attention to anyone or what they do with their stuff. How easy it would be for someone to stroll into that area with a bag, casually add it to the twenty-suitcases-in-waiting, and walk away. The question then came to my mind, how could someone walk into such a place - see wives kissing their husbands goodbye, honeymooners holding hands excited about their vacations, little children toddling about, and mothers embracing their sons arriving safely from their tour of duty in Iraq - and then leave a bomb to blow all those innocent people to bits?

I read Alda's thoughts as I was waiting for my luggage to find its way to the baggage claim at the airport in Baltimore, Maryland. Looking up, I noticed a number of forlorn suitcases waiting patiently for someone to come for them. There were about twenty in all, big and small, strewn about, unattended. Over the loudspeaker came the familiar warning to notify airport authorities if there were any unattended items left about. I looked over at the unclaimed suitcases and I thought, well, yes, there are twenty of them. Being a criminal profiler, I often evaluate a situation from from a criminal's point of view and I found it rather ironic that when we arrive at the airport we watch carefully for suspicious people - at the ticket counter, in the security line, or shopping in the stores - and we become immediately concerned if they suddenly walk away from their luggage, yet when we go down a level to the baggage claim, we don't pay a bit of attention to anyone or what they do with their stuff. How easy it would be for someone to stroll into that area with a bag, casually add it to the twenty-suitcases-in-waiting, and walk away. The question then came to my mind, how could someone walk into such a place - see wives kissing their husbands goodbye, honeymooners holding hands excited about their vacations, little children toddling about, and mothers embracing their sons arriving safely from their tour of duty in Iraq - and then leave a bomb to blow all those innocent people to bits? Since 9/11, I have been in four locations in the world that have been bombed six months to a year after I visited them. I don't mean I was just in the country or a city that was attacked; I mean I was physically present at the exact spot where the bombs exploded. I was in Sharm-el-Sheikh, Egypt walking along the Red Sea boardwalk six months before bombs exploded there. I was in London before the tube attacks, I was in Hyderabad, India nine months before explosions rocked the very place I had visited, and, just recently, bomb blasts killed dozens in Delhi, India, striking a number of

Since 9/11, I have been in four locations in the world that have been bombed six months to a year after I visited them. I don't mean I was just in the country or a city that was attacked; I mean I was physically present at the exact spot where the bombs exploded. I was in Sharm-el-Sheikh, Egypt walking along the Red Sea boardwalk six months before bombs exploded there. I was in London before the tube attacks, I was in Hyderabad, India nine months before explosions rocked the very place I had visited, and, just recently, bomb blasts killed dozens in Delhi, India, striking a number of  sites in the city including Connaught Place, a shopping area which I had visited the night before I left the country. My son, who was with me, went on to Jaipur where, three days later, seven bombs exploded in the downtown area. Luckily, my son was unhurt but too many others were not so fortunate.

sites in the city including Connaught Place, a shopping area which I had visited the night before I left the country. My son, who was with me, went on to Jaipur where, three days later, seven bombs exploded in the downtown area. Luckily, my son was unhurt but too many others were not so fortunate.These bombings hit home for me because I had been there, seen the beauty of those places, seen the faces of the people who worked in the shops, watched the comings and goings and the interactions of the locals and tourists. I had been a part of that landscape. 9/11 no doubt was similar for those in New York City and Washington DC. We ask how anyone could destroy these beautiful places and the people in them?

I sat at BWI airport and stared at those suitcases and thought about Alda's statement. The bomber is doing just what Alan Alda said we need to do to make life meaningful. We must create meaning. We must paint a picture or destroy a picture. We must do something.

The terrorist, the bomber, and the school shooter do what we all do, but they do it as the antihero. A child gets a kick out of building a tower of blocks but he may also get a kick out of smashing it. One can paint a picture or one can douse a canvas in kerosene and light it on fire. Either way, there is a result. If one cannot build or cannot think of a reason to build, then destroying what others build is expressing oneself and effecting change in the world. The school shooter who can't fit in, who sees no future, and feels he cannot "paint a picture" that won't be laughed at, can, on the other hand, shoot down ten classmates and know that the depth of horror over his actions will win him "best in show." The Delhi bombers who don't see themselves as future businessmen can visit Connaught Place after the blasts and feel the thrill of having "beaten their competition."

The terrorist, the bomber, and the school shooter do what we all do, but they do it as the antihero. A child gets a kick out of building a tower of blocks but he may also get a kick out of smashing it. One can paint a picture or one can douse a canvas in kerosene and light it on fire. Either way, there is a result. If one cannot build or cannot think of a reason to build, then destroying what others build is expressing oneself and effecting change in the world. The school shooter who can't fit in, who sees no future, and feels he cannot "paint a picture" that won't be laughed at, can, on the other hand, shoot down ten classmates and know that the depth of horror over his actions will win him "best in show." The Delhi bombers who don't see themselves as future businessmen can visit Connaught Place after the blasts and feel the thrill of having "beaten their competition."My luggage finally came toward me on the conveyor belt. I grabbed my two bags and walked out into the fresh air. I looked back at the crowd inside and hoped that I wouldn't read a headline about that location half a year from now. Unless we find a way for young people to believe they can make a positive impact in the world or at least their small part of it, we will continue to see a number of them become the kind of artists whose work we would prefer to never experience.

If they left a bar of soap in the bathroom, Andrew took a bite out of it. He’d eat any food left behind in the cat’s dish. He ate toothpaste. He once broke a glow-stick and tried to eat it. Hannah and her adoption counselor were seeking help for his condition, known as

If they left a bar of soap in the bathroom, Andrew took a bite out of it. He’d eat any food left behind in the cat’s dish. He ate toothpaste. He once broke a glow-stick and tried to eat it. Hannah and her adoption counselor were seeking help for his condition, known as

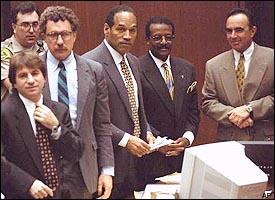

This phone call came during jury deliberations and—in all fairness to the newspaper reporter—he was thinking that because I had been

This phone call came during jury deliberations and—in all fairness to the newspaper reporter—he was thinking that because I had been

by Susan Murphy-Milano

by Susan Murphy-Milano