by Robin Sax

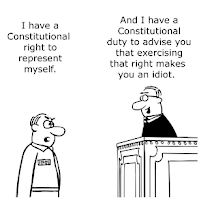

"He who is his own lawyer has a fool for a client” is the proverbial expression warning against self-representation, but is it really true?

A person, or even an attorney, who represents him/herself in a matter is considered a pro per or pro se litigant. Most professionals look down their nose on those who represent themselves. Even non-professionals poke fun and criticize those who represent themselves. So is it really as dumb as people say?

Pro per or pro se representation is not limited to criminal cases. One can represent themselves in civil cases, including family law, in and criminal cases. So why would a litigant or, even more serious, a criminal defendant facing a prison sentence go pro per?

Data from the 1996 report of the Pro Se project overseen by Ayne H. Crawley of the University Of Maryland Law School found that

- 57 percent of pro per defendants said they could not afford a lawyer

- 18 percent said they did not wish to spend the money to hire a lawyer

- 21 percent said they believed that their case was simple and therefore they did not need an attorney

A 1998 ABA-commissioned study found some public beliefs that may influence the choice

- 78 percent believe “it takes too long for the courts to do the job.”

- 77 percent believe “it costs too much to go to court.”

The 1994 ABA Study of Legal Needs found that predominate reasons for low-income households to not seeking legal help were that “it would not help” or “costs too much.” Predominate reasons for moderate-income households to not seeking legal help were that “[issue] not really a problem,” “can handle it on my own” or “a lawyer cannot help.” The Conference of State Court Administrators recently characterized this trend as “unprecedented and showing no signs of abating.”

Research in California indicates that pro per or pro se representation is not solely due to financial limitations. As reported in the National Center on State Courts study of 16 large urban trial courts in 1991 to 1992 – Domestic Relations cases, “a significant portion of the family law pro pers in California are not poor or poorly educated.”

There’s an equally important adage that comes to mind when I think of pro per cases that is not nearly as tired as the "he who has himself as a client" one. That is, "if you want something done right, do it yourself."

It is no secret that lawyers have a bad rap, with complaints of lack of communication, lack of interest, lack of focus, and most commonly, very high fees. It is for these reasons, plus unjust results, slowness of the movement of the system, that make many people mistrust the system. But besides these normal complaints, I often hear criticism that attorneys do not pay attention well enough to learn the facts of the case that they are handling. Or that a client does not feel enough person attention. Plain and simple, pro pers feel that they can do a better job representing themselves because they have more of an understanding of the facts of what occurred.

What does all this say about the work product and slow, or fast, slide of lawyers reputations. I mean think about it, a defendant in a criminal case or a parent in a divorce chooses to forego legal knowledge in favor of knowing the facts of case and thinking that will do better. Is that like people choosing to perform there own medical procedures because they know their own body better and don't need the help of experts? Or is there a distinction?

This may sound silly but it is not. I don’t blame a litigant or defendant for feeling frustrated by their lawyer not knowing whats going on. How can you have faith in the system if the lawyer can’t distinguish one sibling from another in a divorce case or know who was the shooter or who was the master mind in a complex murder/conspiracy case.

So should individuals go pro per or not? Robert Kearns, the American inventor of the intermittent windshield wiper, thought so. Immortalized by the film Flash of Genius, Kearns represented himself in his own patent infringement lawsuits against Ford and Chrysler, to the tune of multi-million dollar verdicts.

But what about the other side? Brandon Moon represented himself during his own rape trial. Even though he was the only blue-eyed, white male in a lineup some 18 months after the rape, the identification was admitted in court and Moon was convicted for a crime he did not commit. Moon spent 17 years in jail before the Innocence Project got him out by proving the DNA was not his. Ted Bundy went pro per as well. It worked out worse for him as the infamous serial killer and former law student was executed on January 24, 1989. The list goes on.

Crawley's study, discussed above, told us that it is true that there has been a "rising tide" of pro se litigants flooding the justice system. And our current court model was designed for a more "traditional" full representation model, whatever that may be. So where does it leave us?

Crawley's study, discussed above, told us that it is true that there has been a "rising tide" of pro se litigants flooding the justice system. And our current court model was designed for a more "traditional" full representation model, whatever that may be. So where does it leave us?Many aspects of the system of justice, from the rules to the training of judges and court staff to the physical layout of the courthouses themselves, have been oriented to cases in which knowledgeable attorneys represent the parties. But if you are considering pro se, there are resources out there for you. In California, you can start with the court's own "Self Help" site.

Tweet

1 comment:

A Solitary Jailhouse Lawyer Argues His Way Out of Prison

Quote: ""'Needle in a haystack' doesn't communicate it exactly. Is it more like lightning striking your house?" says Adele Bernard, who runs the Post-Conviction Project at Pace Law School in New York, which investigates claims of wrongful conviction. "It's so unbelievably hard…that it's almost impossible to come up with something that captures that."

Mr. Collins pried documents from wary prosecutors, tracked down reluctant witnesses and persuaded them, at least once through trickery, to reveal what allegedly went on before and at the trial where he was convicted of the high-profile 1994 murder of Rabbi Abraham Pollack.

The improbable result of that decade-and-a-half struggle was evident on a recent morning in a Midtown Manhattan skyscraper. Mr. Collins sat in a small office he now shares, wearing one of the eight dark suits he owns, a white shirt with French cuffs, a blue-and-gray striped tie and a pair of expensive wingtips. "Every day is beautiful" now, he said, smiling. "I don't have a bad day anymore. I think that my worst bad day out of prison will be better than my greatest good day in prison."

Post a Comment