by Lucy Puryear, M.D.

by Lucy Puryear, M.D.

Mechele Hughes (pictured right) was a very popular young stripper at The Great Alaskan Bush Co. There she made the acquaintance of several men who became enamored of her and showered her with expensive gifts. She was good at her job. One of her admirers, Scott Hilke, asked her to marry him and she said yes. Another man began to shower her with attention and money and he eventually moved in with her. His name was Kent Lippink. He would be murdered with two bullets to his body and one to his face. He too was engaged to be married to Mechele Hughes.

Mechele Hughes (pictured right) was a very popular young stripper at The Great Alaskan Bush Co. There she made the acquaintance of several men who became enamored of her and showered her with expensive gifts. She was good at her job. One of her admirers, Scott Hilke, asked her to marry him and she said yes. Another man began to shower her with attention and money and he eventually moved in with her. His name was Kent Lippink. He would be murdered with two bullets to his body and one to his face. He too was engaged to be married to Mechele Hughes.  John Carlin (pictured left) was the third man intimately involved and infatuated with Mechele Hughes. When Mechele's house needed repairs he invited Mechele and Kent Lippink (pictured together, right) to move in with him and his 16-year-old son, John Carlin, IV. Mechele was engaged to Scott Hilke who was now in Washington, engaged to (so he thought and told his family) Kent Lippink, and on occasion travelling to Europe with John Carlin. This was an odd family to say the least, with Mechele, the successful stripper, at the center of it all. And then Kent was found murdered.

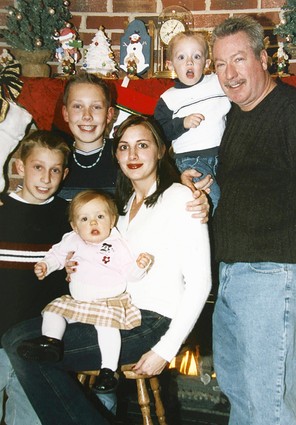

John Carlin (pictured left) was the third man intimately involved and infatuated with Mechele Hughes. When Mechele's house needed repairs he invited Mechele and Kent Lippink (pictured together, right) to move in with him and his 16-year-old son, John Carlin, IV. Mechele was engaged to Scott Hilke who was now in Washington, engaged to (so he thought and told his family) Kent Lippink, and on occasion travelling to Europe with John Carlin. This was an odd family to say the least, with Mechele, the successful stripper, at the center of it all. And then Kent was found murdered.Fast forward to today. Mechele is now Mechele Linehan. She married Colin Linehan, a doctor, in 1998, and they had a daughter in 1999. She had friends, volunteered, and according to her husband, is a wonderful wife and mother. She has also been tried, convicted, and sentenced to 99 years in prison for her role in the murder of her "fiance" Kent Lippink. John Carlin, Mechele's former suitor, has been convicted and sentenced to 99 years in prison for pulling the trigger and killing Kent. Both deny any involvement in his death and are filing appeals.

I don't know if they are guilty or not. Both juries believed so. I invite you to review the evidence for yourself; it's fascinating and certainly is incriminating. But what is more  fascinating to me is how there seem to be two Mecheles.

fascinating to me is how there seem to be two Mecheles.

There's the Michele who was a professional exotic dancer and could manipulate men to fall in love with her and shower her with money and gifts. This Mechele was even able to entice another man to kill for her. (Kent had a life insurance policy with Mechele as the beneficiary that he changed a few days prior to his death.)

Then there's the respectable, upstanding Mechele, married to a doctor, loved by her friends, a model citizen. Colin, her husband, insists that it is an impossibility that the woman he loves and knows better than anyone in the world is capable of murder. He is fighting to have her released. Her friends say they know it is ridiculous to think of her as a "femme fatale," manipulating men and plotting to have them murdered.

Who is Mechele Linehan? Could she be both dangerous and a wonderful and loving woman? Is it possible that her husband is right; the woman he knows is incapable of murder? Maybe he only knows one side of her, the side she allows him to see. How could he not know he was living with someone who could kill?

In psychological terms there is a phenomena called "vertical splitting." Imagine a vertical line drawn straight down the middle of your body, from the top of your head to your feet. This leaves you with two halves, split vertically, a right and a left side. The sides are both part of you, but because you are split in half, sometimes it's easy to ignore what your left side is doing. And because your two sides aren't fully integrated, it's easy to pretend that the left hand that just stole that apple isn't really you—at least it's not part of the right side of you, the side that would never imagine stealing anything.

People use this way of functioning psychologically everyday. An easy example is the pastor who speaks from the pulpit about the evils of homosexuality but is later caught in a clandestine homosexual affair. In the pulpit he is the man he believes he says he is; righteous, moral, and a zealous follower of the Bible.

But when his desires overtake him he is able to put aside the righteous man (split off that part of himself) and allow the other part of him to be fulfilled. He is able for a moment to not think of himself as the man in the pulpit while he is engaged in activity that is abhorrent in one area of his life, but is fulfilling in another. When he is back in the pulpit he is able to ignore or split off his previous actions. And isn't everyone shocked and surprised when they find out? How did we not know? How were we all so taken in?

This happens when people have affairs, but still believe they are good spouses in good marriages, or when people lie, steal, and cheat others (think of Enron), but still go to their kids' little league games and donate money to charity. And the common denominator is that people who are able to use vertical splitting are very engaging, charming, successful, and able to make the rest of us believe they are who we think they are, or who we need them to be. When they are committing adultery or stealing, or worse, they are able to shut out the other reality of their lives and not think about who they may hurting or disappointing. It's almost as if they can believe it never happened, they never did anything wrong, and they are outraged when caught and continue to deny bad behavior.

It is quite likely that Mechele committed this crime. And it is quite likely she will never admit it, never feel remorse for it, and will continue to believe that she had a good life that never should have been interrupted by a trial.

It is quite likely that Mechele committed this crime. And it is quite likely she will never admit it, never feel remorse for it, and will continue to believe that she had a good life that never should have been interrupted by a trial.

Her husband (above, with Mechele) will most likely never believe that the woman he so loves was capable of murder and he will continue to believe that she was wrongly convicted. Her daughter will suffer for the rest of her life missing her Mommy. Kent Lippink will never have his life back because he trusted and loved the wrong woman.

Who are these people? They live next door to you and me, we work with them, we go to church with them, and some of us, like Colin Linehan, are married to them. Tweet