A few years ago I attended a concert with my husband and our two teen-aged boys. After the concert, as we filed passed the aisles toward the exit, a drunk heavy-set man shoved my smaller son out of his way so he could pass in front of us. The shove was violent enough that my son was knocked into me.

Most mothers find, at some point in their lives, that a ferocious beast resides inside of you. This bear of a beast only appears when someone threatens or hurts your child. In my mind, the man was fat, out of shape, just a little taller than me. I could take him down! "Keep your hands off my son!" I growled. My husband and larger son made a path for us to get away from the drunk man. After we arrived safely at our car, the four of us talked about the incident. My two boys and husband described the man as approximately 6-feet-2 inches, muscular, with a pot belly. I saw him as about 5-feet-7 and, in that moment of confrontation, I truly believed I could Wonder-Woman him to the ground. Fueled by adrenalin and an instinct to protect my child, I would have made a lousy witness in this case.

Most mothers find, at some point in their lives, that a ferocious beast resides inside of you. This bear of a beast only appears when someone threatens or hurts your child. In my mind, the man was fat, out of shape, just a little taller than me. I could take him down! "Keep your hands off my son!" I growled. My husband and larger son made a path for us to get away from the drunk man. After we arrived safely at our car, the four of us talked about the incident. My two boys and husband described the man as approximately 6-feet-2 inches, muscular, with a pot belly. I saw him as about 5-feet-7 and, in that moment of confrontation, I truly believed I could Wonder-Woman him to the ground. Fueled by adrenalin and an instinct to protect my child, I would have made a lousy witness in this case.

According to the Innocence Project, eyewitness testimony is responsible for 75 percent of wrongful convictions overturned by DNA evidence. Many eyewitnesses to more serious criminal offenses find themselves in a similar state of nervous system arousal. Adrenalin pumping, heart racing, pupils dilating, your whole system mobilizes to defend or escape. Some people report experiencing the traumatic event as if it were happening in slow motion. You replay it over and over again, in an effort to make sense of it all. Sometimes, in that replay, we fill in the blank spots of the story with false information in order to make the story connect.

For example, imagine you've stopped at a convenience store. In front of you at the check-out line is a person wearing a dark sweatshirt with a hood. You're looking around the store, wondering if you need to get anything else, when you hear a loud boom. You look back and the person in the hoody is reaching over the counter and pulling money out of a cash register. You look around for a place to hide. Other customers are screaming and shouting different things. "He's getting away! The clerk's been shot." Out of the corner of your eye you see a dark-blue car speed out of the parking lot. Some time later, the police arrive and begin to interview the witnesses. You tell the police that a man pulled a gun, shot the clerk, took money out of the register, and sped away in a dark-blue car.

The clerk gets up from behind the counter and starts to cry. She thought she had been shot. No blood, no bullet, no injury. A witness from outside the store said he saw a large woman in a hooded sweatshirt run out of the store and down a back alley. That witness also saw a black truck speed away in the opposite direction. What did you actually see? The back of a person, could be male or female, in a hooded sweatshirt, took money out of the register, and a dark-colored vehicle sped away. The gender, age, and race of the thief, the source of the loud boom, and the method of get-away are still unknown.

The clerk gets up from behind the counter and starts to cry. She thought she had been shot. No blood, no bullet, no injury. A witness from outside the store said he saw a large woman in a hooded sweatshirt run out of the store and down a back alley. That witness also saw a black truck speed away in the opposite direction. What did you actually see? The back of a person, could be male or female, in a hooded sweatshirt, took money out of the register, and a dark-colored vehicle sped away. The gender, age, and race of the thief, the source of the loud boom, and the method of get-away are still unknown.

Your eyewitness statement was contaminated by the normal human need to connect the dots of a story, to make sense of a situation. You heard another witness say, "He's getting away," so you assumed the perpetrator was a man. The loud boom, and the fact that you could no longer see the clerk, made you assume she had been shot. This story emphasizes the need for law enforcement officers to interview witnesses as soon as possible after an event, and interview them individually. As tiresome as that process feels to the witnesses, it does help prevent the confabulation of memories as people influence one another to fill in the missing pieces of the story.

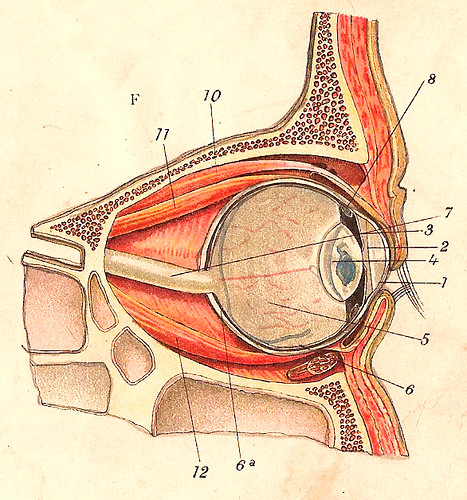

When we see things out of our peripheral vision, color vision is distorted. The cells in our eyes that perceive color, called cones, fade out in our peripheral vision. If you don't see something head on, you will often mistake the color. As we age, our night vision gets poorer as we lose the more sensitive rod cells. These cells are responsible for motion detection and night vision. The rods are highly sensitive to motion, so you can block something flying toward your head. In the eyewitness example, if you see something out of your peripheral vision you likely will get the color wrong, unless you also see it straight on, in good light, with normal color vision.

When we see things out of our peripheral vision, color vision is distorted. The cells in our eyes that perceive color, called cones, fade out in our peripheral vision. If you don't see something head on, you will often mistake the color. As we age, our night vision gets poorer as we lose the more sensitive rod cells. These cells are responsible for motion detection and night vision. The rods are highly sensitive to motion, so you can block something flying toward your head. In the eyewitness example, if you see something out of your peripheral vision you likely will get the color wrong, unless you also see it straight on, in good light, with normal color vision. The recent execution in Georgia of Troy Davis, convicted of murder based solely on eyewitness testimony, should give us all cause for concern. Seven of the 10 eyewitnesses to the crime either recanted or significantly altered their testimony. Despite the significant holes in the case, Troy Davis was executed on September 21, 2011. The family of murder victim Officer Mark Mac Phail reportedly saw "nothing to rejoice about" in the execution of Troy Davis. Hopefully, they will find some peace and healing.

The recent execution in Georgia of Troy Davis, convicted of murder based solely on eyewitness testimony, should give us all cause for concern. Seven of the 10 eyewitnesses to the crime either recanted or significantly altered their testimony. Despite the significant holes in the case, Troy Davis was executed on September 21, 2011. The family of murder victim Officer Mark Mac Phail reportedly saw "nothing to rejoice about" in the execution of Troy Davis. Hopefully, they will find some peace and healing.Officer Mac Phail, jumped to the aid of a homeless man who was being attacked. He was murdered trying to save the life of a stranger. He is survived by a wife and two young children who will never get to know their father. I hope justice, not merely vengeance, prevailed in this case.

Photos courtesy of: Looking glass, CGoulao, and Clearly Ambiguous

Tweet

4 comments:

Truth is sometimes scary to accept. But we have to face it.

"Officer Mac Phail, jumped to the aid of a homeless man who was being attacked."

So, according to witnesses, did Troy Davis. He had no weapon, however his accuser (and allegedly the person who intimidated other witnesses) owned the same caliber weapon as that which felled Mark MacPhail.

Great analysis of the troubling Troy Davis case.

Thank you for your comments. Many other factors can distort the accuracy of eyewitness accounts, including personal bias. It's important to learn all we can about the limits of human observation to lesson the likelihood of convicting an innocent person.

Post a Comment