by Deborah Blum

When I was researching my book, The Poisoner's Handbook, I started by making a list of famous homicidal poisons: cyanide and strychnine, arsenic and antimony. The resulting catalog quickly outgrew my plans for a book of relatively modest length. How would I decide which toxic substances belonged in my particular handbook?

Since my story was of two somewhat renegade scientists trying to establish - or more accurately, invent - the profession of forensic toxicology in Prohibition-era New York, I started researching poison homicides in that time period. I focused on murders from about 1918 to 1935 in that remarkable city. I wasn't looking for famous cases - it was murder as a fact of everyday life that interested me. Those small, slipped-away stories, the cases that haunted me, the lives altered that I couldn't forget, ended up defining my poisonous history of early 20th century America.

And that's why the chapter on arsenic began with a long-forgotten mass murder:

The weather, that summer of 1922, held steady at what the newspapers like to call “fair”, the skies a gas-flame blue, the temperatures hovering near 80 degrees. On the last day of July, as Lillian Goetz’s mother would forever recall, the morning was another warm one. She offered to make her daughter a box lunch, but Lillian refused. It was too hot to eat much; she’d just grab a quick sandwich at a lunch counter.

The 17-year-old daughter worked as a stenographer in a dress goods firm, occupying a small set of offices in the Townsend Building, at the bustling corner of 25th and Broadway. There were plenty of quick eateries nearby, tucked among the offices and shops and small hotels. Lillian, like many of her co-workers, often just stepped over to Shelbourne Restaurant and Bakery, just a half block south on Broadway.

The Shelbourne catered to the office trade, opening in the morning, closing in the early afternoon. Stenographers and secretaries in their bright summer hats and stylish short skirts, businessmen and office managers in their dark tailored suits crowded daily along its wooden counters and small square tables, hurrying through a meal of coffee, hot soup with fresh-baked rolls, sandwiches, and slices of the bakery’s renowned peach cake and berry pie.

According to police reports, on July 31, Lillian ordered a tongue sandwich, coffee, and a slice of huckleberry pie. It was the pie that killed her.

Five other people died as well and more than 60 went to the hospital that day. The scream of ambulances down Broadway was so constant that people called the police department thinking the city had caught fire. The lead suspect - although he would never be charged - was a baker at the Shelbourne, who'd caught a false rumor that he was about to be fired.

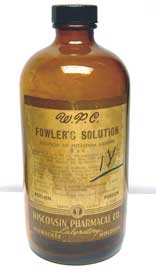

Arsenic, at the time, was remarkably easy to acquire. It was used in popular rodent poisons (my favorite had the very direct name Rough on Rats). It was used as a tonic, in brands such as Fowler's Solution. It was beloved by poison murderers because it was odorless and mostly tasteless. In a white powdery form, like arsenic trioxide, it folded almost invisibly into pastry dough.

Today, thanks to improved regulations, arsenic cannot be so casually acquired. Nor is it in the same homicidal demand. Forensic toxicology has made arsenic far too detectable a means of death. It's been identifiable in a corpse for well over 100 years, these days, in the barest trace amounts. And as a metallic element, it remains in the body (notably in the hair) for centuries. It serves, in fact, as a indelible marker of murder.

The fascinating, twisted story of arsenic then was an obvious choice for my book. The tale of little Lillian Goetz maybe less so. But there was this moment of heartbreak that just stayed with me. I read countless news stories about the Shelbourne killer. There's a moment, in one of them, in which her mother, Anna Goetz, is talking to the police about that rejected box lunch, caught at that point in which she knows, she's sure, that she could saved her daughter's life if she'd only insisted on that homemade meal.

Oh, I could see myself - the working mother of two boys - caught in that same moment, replaying that loop in which I might have rescued my child, could have kept her alive, kept him alive, if I'd only done things differently. One of the tasks that I'd set for myself in the book was - despite my real fascination with the wicked chemistry of poisons - to never glorify the subject. Poisoners represent human evil in my story. A lost child like Lillian reminds us of that, should remind us of that.

Still, when I received an e-mail recently with the subject line "Lillian Goetz", I had a moment where I worried that someone in the family didn't agree with me. In that, I was wonderfully wrong. The message came from Lillian's nephew Steve Goetz, a physiology teacher, and he wrote: When I began the chapter in your book covering arsenic, I was amazed to see Lillian Goetz's story featured. I had never realized that her death was a part of such a large and publicized event. Lillian was my aunt, my father Nelson's older sister. Her death by poison was rarely mentioned in the family, and most of the details were vague.

But though they rarely spoke of her, she was always there, a ghost in the house. Her death rewrote the way they lived. Steve was born in 1943 at Bronx Hospital, the facility that treated the dying girl: When my Grandfather, Lillian's father William Goetz, visited my mother who had given birth to me in 1943 at Bronx Hospital, he told her how very sad he felt revisiting the place. After Lillian's death, her parents (William and Annie) discarded all religious items in their house and were non-observant Jews from that point on. My grandmother Annie rarely left her apartment as long as I knew her, and my 98 year old mother told me the other day that that was also true since at least the early 1930's, when she first met Annie.

Steve also sent me the photograph that I've put at the top of this post. His grandmother, Annie Goetz is in the middle, with a very young Lillian holding one hand and her brother Nelson (Steve's father) holding the other. He even sent an image of the back of the photo, all names carefully written in that lovely cursive handwriting of the past with its lacy capital letters.

I've found myself studying their serious faces, taken during an era when people so rarely smiled for photographs. I've pondered Lillian's sober little face under that white hat, imagined her growing up into a dedicated, responsible young woman. But I know that doesn't really do her justice.

I wrote back to Steve Goetz, asking him if I could share the photo and family information and he answered me in the kindest way: "I had rarely thought about Lillian for most of my life - she seemed to be such a distant figure. I want to thank you for bringing her to life for me as a real person, in a way she had never existed for me before. My only tenuous link to her is her copy of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which I've had for many years. It contains a bookmark, a cut-out yellowed newspaper column called Our Rhyming Optimist. Aline Michaelis published 6 poems a week for her column from 1917 for the next 17 years. The poem Lillian saved is called "You Have Come Back."

Since I learned about, and was given the book, I've been intrigued that my aunt, coming from a family that seemed not to place a high priority on education or reading, should have this book of poetry. I've always felt that she must have been an interesting and sensitive person, that I would have liked to have gotten to know."

So this one's for you, Lillian. In remembrance, and regret. And a wish that you'd never ended up in my book.

Tweet