Forensic entomology, the study of bugs as related to death, is a relatively new science. In the past, investigators thought bugs were a nuisance, something to be washed away or disposed of as quickly as possible. But the relationship between dead bodies and maggots is nature’s way of recycling—the way a corpse becomes simple organic matter.

Death carries a universal scent that attracts hundreds of insects and other arthropods as they set about the body to feed and lay eggs (usually in the bloody areas first). The life cycles of the insects that take place on the deceased are fixed and precise. Those characteristics make it a good tool for investigators called forensic entomologists.

It’s funny then how a form of forensic entomology was practiced as early as the thirteenth century, yet took so lo ng to come to fruition. Story has it that a murder in a Chinese village was the result of the victim being repeatedly slashed. Witness questioning was going nowhere. In frustration, the magistrate ordered all the village men to assemble, each bringing his own sickle. Standing in the hot summer sun, flies were attracted to just one sickle because of the blood residue and tissue fragments clinging to the blade and handle. Confronted with this evidence, the owner of the sickle confessed to the crime.

ng to come to fruition. Story has it that a murder in a Chinese village was the result of the victim being repeatedly slashed. Witness questioning was going nowhere. In frustration, the magistrate ordered all the village men to assemble, each bringing his own sickle. Standing in the hot summer sun, flies were attracted to just one sickle because of the blood residue and tissue fragments clinging to the blade and handle. Confronted with this evidence, the owner of the sickle confessed to the crime.

Insects have helped to solve many crimes. The unique activities of the insects, paired together with the arrival of different species and different forms of species, act as a predictable time-clock that can be traced backward for estimations. The order in which the insects arrive is called succession. Succession is the idea that as each organism or group of organisms feeds on a body, it changes the body and makes it attractive to the next group, and, so on. For example, within ten minutes after a body is dead in open air, flies arrive and lay thousands of eggs in the mouth, nose and eyes of the corpse. The eggs hatch into larvae, also known as maggots, in twelve hours up to three days and the maggots feed on tissues. Since maggots go through three phases on their way to becoming adult flies, the entomologist tracks their development and makes calculations backwards in order to determine the date and time the eggs were most likely deposited.

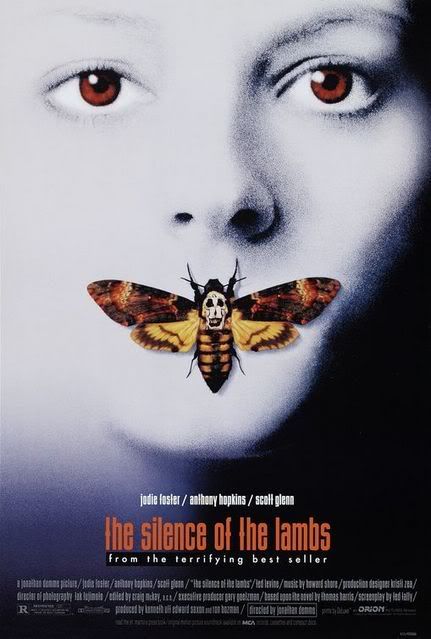

The Importance of Blow Flies

Death carries a universal scent that attracts hundreds of insects and other arthropods as they set about the body to feed and lay eggs (usually in the bloody areas first). The life cycles of the insects that take place on the deceased are fixed and precise. Those characteristics make it a good tool for investigators called forensic entomologists.

It’s funny then how a form of forensic entomology was practiced as early as the thirteenth century, yet took so lo

ng to come to fruition. Story has it that a murder in a Chinese village was the result of the victim being repeatedly slashed. Witness questioning was going nowhere. In frustration, the magistrate ordered all the village men to assemble, each bringing his own sickle. Standing in the hot summer sun, flies were attracted to just one sickle because of the blood residue and tissue fragments clinging to the blade and handle. Confronted with this evidence, the owner of the sickle confessed to the crime.

ng to come to fruition. Story has it that a murder in a Chinese village was the result of the victim being repeatedly slashed. Witness questioning was going nowhere. In frustration, the magistrate ordered all the village men to assemble, each bringing his own sickle. Standing in the hot summer sun, flies were attracted to just one sickle because of the blood residue and tissue fragments clinging to the blade and handle. Confronted with this evidence, the owner of the sickle confessed to the crime.Insects have helped to solve many crimes. The unique activities of the insects, paired together with the arrival of different species and different forms of species, act as a predictable time-clock that can be traced backward for estimations. The order in which the insects arrive is called succession. Succession is the idea that as each organism or group of organisms feeds on a body, it changes the body and makes it attractive to the next group, and, so on. For example, within ten minutes after a body is dead in open air, flies arrive and lay thousands of eggs in the mouth, nose and eyes of the corpse. The eggs hatch into larvae, also known as maggots, in twelve hours up to three days and the maggots feed on tissues. Since maggots go through three phases on their way to becoming adult flies, the entomologist tracks their development and makes calculations backwards in order to determine the date and time the eggs were most likely deposited.

The Importance of Blow Flies

Blow fly eggs, collected from human remains and analyzed, can provide investigators with an accurate estimate of time between death and discovery and allow them to better target their investigative efforts.

Blow fly eggs are small (2 to 3 mm), whitish-yellow, and somewhat elongate. During warmer seasons they are easily visible to the naked eye found packed into natural body openings and wound sites in large numbers. During colder months, however, their numbers may be few and difficult to locate, buried within recessed locations. Blow fly eggs typically hatch within one to three days depending on species and environmental conditions. Dissection of egg samples and analysis of the stage of embryonic development may further depict the time since oviposition—creation—and, therefore, the time of the victim’s

Blow fly eggs are small (2 to 3 mm), whitish-yellow, and somewhat elongate. During warmer seasons they are easily visible to the naked eye found packed into natural body openings and wound sites in large numbers. During colder months, however, their numbers may be few and difficult to locate, buried within recessed locations. Blow fly eggs typically hatch within one to three days depending on species and environmental conditions. Dissection of egg samples and analysis of the stage of embryonic development may further depict the time since oviposition—creation—and, therefore, the time of the victim’s  death.

death.

Within 24 - 36 hours, beetles arrive and feast on the dry skin. After 48 hours, spiders, mites, millipedes, and wasps arrive to feed on the bugs that are already there. Entomologists today recognize six decomposition stages.

Bug behavior can also indicate whether the victim was killed indoors or out, during the day or night, in warm or cold weather, in shade or sun. Bugs scattered and laying dead near remains have also told the story of a women who died from a drug overdose. The cocaine chemicals within her body had been passed onto the bugs.

Case Story: Insect Trail

Blow fly eggs are small (2 to 3 mm), whitish-yellow, and somewhat elongate. During warmer seasons they are easily visible to the naked eye found packed into natural body openings and wound sites in large numbers. During colder months, however, their numbers may be few and difficult to locate, buried within recessed locations. Blow fly eggs typically hatch within one to three days depending on species and environmental conditions. Dissection of egg samples and analysis of the stage of embryonic development may further depict the time since oviposition—creation—and, therefore, the time of the victim’s

Blow fly eggs are small (2 to 3 mm), whitish-yellow, and somewhat elongate. During warmer seasons they are easily visible to the naked eye found packed into natural body openings and wound sites in large numbers. During colder months, however, their numbers may be few and difficult to locate, buried within recessed locations. Blow fly eggs typically hatch within one to three days depending on species and environmental conditions. Dissection of egg samples and analysis of the stage of embryonic development may further depict the time since oviposition—creation—and, therefore, the time of the victim’s  death.

death.Within 24 - 36 hours, beetles arrive and feast on the dry skin. After 48 hours, spiders, mites, millipedes, and wasps arrive to feed on the bugs that are already there. Entomologists today recognize six decomposition stages.

Bug behavior can also indicate whether the victim was killed indoors or out, during the day or night, in warm or cold weather, in shade or sun. Bugs scattered and laying dead near remains have also told the story of a women who died from a drug overdose. The cocaine chemicals within her body had been passed onto the bugs.

Case Story: Insect Trail

The body of a woman was found in a wooded area near the District of Columbia. There appeared to be no evidence of foul play but as part of police procedure, the scene was photographed. It was late summer and the dead woman was dressed in a tube top and slacks. Since her clothes were intact the possibility of a sexual assault was not taken into account.

Despite peaceful surroundings, her advanced stage of decomposition meant that the medical examiner would have a difficult task. The body had been lying out in the open for about ten to twelve days. Larvae were in the eyes, around the nose and mouth, in the chest area, and on the palms of both hands. The dead woman was identified immediately and because of the condition of the body, pressure was put on the authorities to release her corpse for a speedy burial. A limited autopsy indicated the cause of death was unknown and the body was turned over to the undertaker.

Typically, that would have ended the investigation, but one detective remained puzzled. The question about time of death bothered him. The victim had been reported missing a few days before her body was discovered on the trail, but the detective wondered, why was her body so badly decomposed? And because of the advanced decay, her autopsy had been less than exact. Finally, three years later, the detective contacted a forensic anthropologist, showed him the photographs and asked for a second opinion.

The anthropologist asked all the normal questions and studied the photographs. He told the detective that considering the time of year, the larval activity in the photographs was consistent with the medical examiner’s time of death estimate and asked if police had a suspect. The detective was dumbfounded. He explained that the lack of evidence for violence led them to rule out murder and they hadn’t bothered to look for suspicious persons.

“Of course there’s evidence,” the scientist said, pointing to the pictures, “You just showed it to me.” Because of his forensic training, he had immediately recognized the significance of the larval activity in the palms of the hands. In the pictures the surfaces on both arms were clearly free of maggots, but the flies had laid their eggs in the deep lesions across the width of her palms. This signifies the kind of injury that is associated with someone who is defending against a knife attack.

just showed it to me.” Because of his forensic training, he had immediately recognized the significance of the larval activity in the palms of the hands. In the pictures the surfaces on both arms were clearly free of maggots, but the flies had laid their eggs in the deep lesions across the width of her palms. This signifies the kind of injury that is associated with someone who is defending against a knife attack.

The detective was stunned. “But how can you be sure the hand injuries aren’t just something that happened when she fell?”

He pointed to the chest area in the top photo. The decomposition, he said, suggested something else. “Maggots don’t swarm like that unless they have something to feed on. . . . Look at the body, I think you’re going to find she was stabbed in the chest.”

After much persuading, the detective convinced other officials. Her body was exhumed by lantern light in the middle of a snowstorm. This time the examination was more complete. Soft tissue was simmered away gently for a clearer view. Unmistakable blade patterns were found in the bones of the hands and in the chest. A new death certificate was issued, and the manner of death reclassified to homicide. Homicides are one crime where there is no statute of limitations. As long as the case is unsolved, it is considered open to scrutiny and further investigation.

Despite peaceful surroundings, her advanced stage of decomposition meant that the medical examiner would have a difficult task. The body had been lying out in the open for about ten to twelve days. Larvae were in the eyes, around the nose and mouth, in the chest area, and on the palms of both hands. The dead woman was identified immediately and because of the condition of the body, pressure was put on the authorities to release her corpse for a speedy burial. A limited autopsy indicated the cause of death was unknown and the body was turned over to the undertaker.

Typically, that would have ended the investigation, but one detective remained puzzled. The question about time of death bothered him. The victim had been reported missing a few days before her body was discovered on the trail, but the detective wondered, why was her body so badly decomposed? And because of the advanced decay, her autopsy had been less than exact. Finally, three years later, the detective contacted a forensic anthropologist, showed him the photographs and asked for a second opinion.

The anthropologist asked all the normal questions and studied the photographs. He told the detective that considering the time of year, the larval activity in the photographs was consistent with the medical examiner’s time of death estimate and asked if police had a suspect. The detective was dumbfounded. He explained that the lack of evidence for violence led them to rule out murder and they hadn’t bothered to look for suspicious persons.

“Of course there’s evidence,” the scientist said, pointing to the pictures, “You

The detective was stunned. “But how can you be sure the hand injuries aren’t just something that happened when she fell?”

He pointed to the chest area in the top photo. The decomposition, he said, suggested something else. “Maggots don’t swarm like that unless they have something to feed on. . . . Look at the body, I think you’re going to find she was stabbed in the chest.”

After much persuading, the detective convinced other officials. Her body was exhumed by lantern light in the middle of a snowstorm. This time the examination was more complete. Soft tissue was simmered away gently for a clearer view. Unmistakable blade patterns were found in the bones of the hands and in the chest. A new death certificate was issued, and the manner of death reclassified to homicide. Homicides are one crime where there is no statute of limitations. As long as the case is unsolved, it is considered open to scrutiny and further investigation.

Excerpted from Detective Notebook: Crime Scene Science

graphic: Cleveland Museum of Natural History

5 comments:

Very interesting. This type of science is so fascinating. I really enjoyed the story of the sickle. Quite clever.

I liked the story of the woman in D.C. If only all detectives were as conscientious. Though disturbing a grave is....disturbing....it took that for justice to be served. Worth digging deeper!

I am reading a most interesting book called 'Corpse - Nature, Forensics, and the Struggle to Pinpoint Time of Death' by Jessica Snyder Sachs. In it there are a couple of chapters on bug sleuthing - very interesting reading all round and very well written.

'Anon'

txmichelle,

Thanks, that's one of my favorite stories. It was in a Chinese book written by Song Ci in the Song Dynasty and was called: The Washing Away of Wrongs.

I'm using it in a book I'm working on now. Got's to recycle good stories.

Cheers,

Andrea

Anonymous,

Thanks for the tip about the book, I'll have to keep an eye out for it.

The DC story came from an anthropologist and I thought it was cool.

Thanks for reading me!

Cheers,

Andrea

Post a Comment